This is part of a series: Njeddo Dewal, Mother of Calamity

Njeddo Dewal, Mother of Calamity

Story, story, tell us a story!

Let me lie down on my back with my ankle crossed above my knee,7 dive into the sea of words and crawl in it with big arm strokes.8

I will swim there, my feet slapping the water with a sound of puntupanta.9

What I am about to say is more wonderful than a dream! But it is not humbug or tomfoolery. The tongue bursts with speech. But there is no trickery that moves my tongue. It resounds more clearly than a royal bell. It shows the way better than a trusted guide.

My words will interest all those who are gifted with intelligence, all those who meditate and reflect.

7 Traditional relaxation position (pantal) in which lying on one’s back, one leg is bent with the sole flat on the ground, while the other leg bends horizontally with the knee facing outwards drawing a right-angled triangle, crossing the first leg above the knee. In Eastern yoga this is a variation of Eye of the Needle pose (Sanskrit: Sucirandrasana) with the sole of the bottom foot flat on the ground. It is a relaxing hip-opener.

It was our grandfather Bouytôring11 who first had this tale told through a skull to his son Hellêrè and it lasted seven weeks. This is what happened.

11 Bouytôring is one of the most famous of the great Fulɓe ancestors. He was especially popularised in the Fulɓe tradition of Djêri, in Senegalese FerIo (a region of Linguére). He is often introduced as son of Kîkala, the first man. The stories about him were mainly transmitted to me by the great traditional masters Ardo Dembo and Môlo Gawlô (see endnote 78).

Bouytôring seized his shepherd’s staff, carved from the sacred nelbi tree (2). It was certainly no ordinary staff.

There are three kinds of nelbi: the nelbi that grows in solid ground, the nelbi that grows in water, and the nelbi that grows nowhere, in neither earth nor water. This mysterious nelbi needs neither water nor compost to spring forth. Whether the winter is mild or harsh, it bears fruit. Whoever holds in his hand a staff from this miraculous wood can tell the future without error. In the green branches of the nelbi-from-nowhere flows a sap of fire. It is from one of its branches that Guéno cut the first shepherd’s staff that he gave to Kîkala, the first man. It is this very staff that was passed down from father to son until Bouytôring.

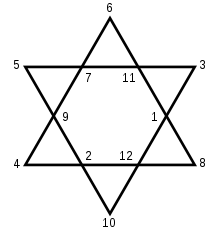

So Bouytôring seized this miraculous staff, from a no less miraculous tree, and traced on the ground the figure of a hexagram or six-pointed star (3).

Then he brought out a human skull (4), which had also been passed down to him from father to son, and placed it in the central cell of the hexagram. Sitting in this hexagonal centre with his son, he ignited the skull and the latter began to speak...

For seven weeks, Bouytôring and his son listened to the skull, each week taking place in a different one of the seven cells of the hexagram.

It is this telling which was recorded and preserved in memory. Bouytôring made a tale of it that Hellêrè collected and recited in order to transmit it for posterity.

It is this tale, coming from the depths of time, that in my turn I am going to unfurl to you.

Hark, listen to me! I am going to tell you the tale told by Bouytôring and Hellêrè.

I will not recite in mergi to a rhythmed beat, but in fulfulde maw’nde, the

great Fulfulde prose.12

12 Mergi: poetry to a rapid rhythm; fulfulde maw’nde: prose

Endnotes:

(2) nelbi (sunsun in Bambara, diospyros mespiliformis): Fruit tree with medicinal properties. It is the sacred tree of the Fulɓe, associated with male activities; the shepherd’s staff is always taken from a branch of this tree. The kelli, another sacred tree, is related to feminine activities.

In African tradition, there are four staffs: the shepherd’s staff, the staff of command, the staff of wisdom and the staff of old age.

(3) hexagram: Known in English as the star of David and associated with the Jewish mysticism of the Kabbalah, its origin is much older as a universal esoteric and religious symbol in Abrahamic and Indic religions as well as among the Fulɓe. It is composed of two equilateral triangles that interlock, one facing upwards (sky), the other downwards (earth). The whole constitutes a six-pointed star. The intersecting lines form six peripheral triangular cells and a central hexagonal cell (or box), called the “navel” or “heart” of the hexagram.

The Fulɓe name for the hexagram is faddunde ndaw (from faddaade: to protect, ndaw: ostrich). It is said that the ostrich, before laying eggs, traces the figure of a hexagram by dancing on the ground, then comes to lay its eggs in the middle of this sign. By analogy, when a Fulɓe encampment is to be established, the leader of the convoy reproduces this sign, on horseback or on foot, around the encampment. The silatigis (Fulɓe initiates, see endnotes 5 and 16) also use it for divination.

For the Fulɓe and Bambara, it is a figure of great protection. It symbolizes the universe. The triangle whose point is at the top represents fire and the one whose point is at the bottom represents water. The six points represent the four cardinal directions, plus the zenith and the nadir. The seven cells represent, among other things, the seven days of the week, and the twelve points the twelve months of the year.

In Hinduism it is known as the Shatkona, and as well as the above symbolism of the meeting of sky and earth, it is also understood as the marriage of masculine and feminine, the union of the god Shiva and his feminine dimension Shakti. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, as well as the Star of David, it is also known as the Seal of Solomon. In Muslim esotericism, the hexagram is considered as the geometric spelling of the great name of God: Allâh. The last letter, the "hâ" (whose stylized shape is that of a triangle), is used to form the rising triangle, known as the “triangle of fervour”. The vertical elements of the other three letters (alif-lam-lam) serve to form the descending triangle, or “triangle of Divine Mercy”. For the Muslim initiate, the hexagram is therefore not considered as an exclusively Hebrew symbol, but as an eternal symbol representing the union of earth and heaven, in other words the contingent soul and transcendent God.

(4) skull: The Korê school (Mandinka traditions preserved especially among the Bambara) studied the bones of the head and gave a name to each of them, as did the Fulɓe masters of Djêri (Senegal) who were attached to the cult of Dialan. The latter know a rite of invocation of the skull that allows them to predict the future. The skull is considered to be the receiving agent of celestial forces. Among all skulls, the skull of man is supposed to be the best agent for the reception and transmission of these forces. The skulls of chiefs or men of high repute are preserved not only as trophies, but also as agents capable of transmitting virtues of these great men who have disappeared to the living. These brief remarks will allow us to better understand the essential function that the “sacred skull” will play throughout this tale.

According to the Bambara teaching of the “Komo” particularly those from Dibi of Koulikoro (on the left bank of the Niger downstream from Bamako), the human body comprises seven centres distributed between the top of the head and the base of the body. The skull is considered the “head centre”, with the other six centres following one another from the forehead down — one cannot help but draw parallels with the seven chakras, or energy centres, which Hindu tradition also describes on the human body, from the top of the head to the base of the spine.

On African initiation altars, we find a number of pottery vases: three, five or seven. When there are seven, they represent the seven centres of the body. In the vase representing the skull, four “thunderstones” are placed: these symbolise the celestial fire that came down to Earth to carve, in the beings that populate it, intelligence and strength emanating from Mà- n’gala (God).

From another perspective, the skull is associated with the cosmic egg, which potentially contained all things before the creation of the contingent world. As such, the skull symbolises the matrix of knowledge.

In Fulɓe tradition, the nine main bones of the skull are like the nine paths of initiation. The ninth is not visible, nor is the extra “one”, which is not considered a number because it is the unknowable and indeterminable Unity. The secret of the knowledge of this bone is linked to the secret of this fundamental and indivisible Unity, harking back to the Unity before the creation of the contingent world.

Translation from Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Contes initiatiques peuls

Image: Fred the Oyster’s Magic Hexagram

No comments:

Post a Comment