This is part of a series: Njeddo Dewal, Mother of Calamity

Paradise Lost

There were no worries. Death was rare, offspring were numerous, sickness unknown. Everyone was healthy. Even the old with white hair kept their vigour untroubled by fever, cough or infirmity.

The animals too were untroubled by disease, safe from exhausting diarrhoea, lung infections, or stinging insects. In the fields, locusts did not devastate the crops.

In this blessed country, where death was rare and men of knowledge abundant,3 poverty did not exist. Even those who only owned two herds inspired pity and were thought to be miserable. In Heli and Yoyo, locusts only came to scour the fields after the harvest was done. Such was the land where the Fulɓe lived, rich and happy!

3 Men of knowledge (gando from andal) were wise in the total sense of the term, both in theory and in practice and in every field of knowledge. Their knowledge encompassed the external world just as much as the hidden meaning of things (see endnote 5).

On the horizon were mountain ridges whose curves extended one after another in a harmonious display of overlapping peaks that took one’s breath away. The flood valleys were full of lakes teeming with freshwater fish and covered with water lilies (6) and other flowers in full bloom, seeds as numerous as millet grains and succulent berries, so sweet that they did not sting the gums.

In the high bush, graceful doe and majestic great buffalo lived in peace, for there were no wild beasts of prey and the cities did not harbour hunters.

The country was so loved by Guéno that if the moon, sulking, abandoned its home, saying “I will not return”, bright stars appeared, piercing the sky like bright embers used for cooking food, so as to illuminate the heavens and the homes of men.

In the Wâlo, powerful silk-cotton trees stood side by side with large baobabs, as if to watch together the great mahogany trees (7) spread their bulky branches from which precious timber was logged.

The fertile plains were as vast as the heavens.

The undulating rivers and streams that watered the land were innumerable.

Over here, sandbanks tumbled down into the river as if to wash themselves clean.

Over there, wooded hills, rich in avifauna, came to dip their feet in the water as if to soak their legs up to their knees. Their gentle slopes hugged the meandering river, seemingly accompanying the waves to their nuptial home.

Nature abhors uniformity,4 and sometimes stone dams seemed like they wished to stop the water’s inevitable course from continuing to its final destination: the great salt sea. But water, that soulless mother element (8), is the very embodiment of patience and strength. When an obstacle blocks its path, it first rises without rushing to cover it. Then it leaps up, dispersing a cloud of droplets as if to make believe it was the coming of the gatamare, the first tornado of the year. Part of this water cloud evaporates into vapour, but a vapour which does not block the nostrils nor impede breathing, the rest of it gathers below it, forming a beautiful foaming white band of water that resumes its course and rolls towards its goal, nibbling at the riverbanks to increase its wingspan (9) and excavating the riverbed.

4 Lit. “God does not create two [identical] things”

On the river verges, the water vapour humidified the atmosphere so nicely that anyone who approached felt their body refreshed and experienced in that moment an irresistible urge to sleep, and drop down into the land of dreams.

In short, the country was so pleasant that the foreigner who set foot in it forgot to return home!

The griots of Heli and Yoyo sang at length about this wonderful country. They called it the “Septenary Land” (10), because seven great rivers meandered through seven high mountains and there were seven great sandy plains with beautiful dunes that rolled down like frozen waves.

In addition to the almond tree, the fruit trees that populated the bush had seven dominant species: the acacia tree with edible fruit; the date palm whose tightly packed bunches produced a fruit sweeter than the best honey; the jujube tree a single fruit of which could fill the most enormous mouth; the tamarind tree whose fruit cured every disease imaginable (11); the palmyra palm a single fruit of which could satiate an elephant; as for the fig tree, to try to describe its fruit could not do justice to its value; finally, oh yes! in the land of Heli and Yoyo, each shea tree gave enough butter to feed a whole village neighbourhood for a year! These seven blessed trees produced an abundance of fruit that could be harvested throughout the year.

Butter was not uncommon in this country; it was not only obtained from the shea tree but also from the m’pegou tree, not to mention the creamy butter provided by the opulent cows. Groundnuts5 from the plains and sardines from the rivers provided all the necessary oil.

As for honey with its delicious flavour, it was so abundant that it was not sold.

In family or small individual plots of land,6 pumpkins and corn, large squash, sweet watermelons and delicious coarse beans were harvested. Pumpkins and beans crawled and overlapped each other so bountifully that they would cover the thatched roofs in all seasons, preventing smoke from passing through them into the atmosphere.7

In each city, in each small village, the cries of the cockerels echoed (12). The barking of dogs was as canorous as the sound of trumpets, and the braying of donkeys did not offend the ear. The oxen (13) roared as if to draw attention to their beauty and stoutness. As for the bleating of goats soliciting their females, it was like a concert of beautiful human voices.

Indeed, it was the country where, to wake the inhabitants, the harmonious braying of donkeys responded to the pleasant cockerels’ calls over the background symphony of nocturnal birds returning to their nests.

In Heli and Yoyo, bats blinded by the nascent light of day did not get dazed and caught in thorns.

In Heli and Yoyo, the termites chewed on the stalks of grain, not on their ears: they did not did not gnaw at human affairs.

In a word, nothing in this country could cause harm. Neither scorpion nor snake venom ever killed, nor even caused a swelling.

The sky in the land of Heli and Yoyo was the lightest shade of indigo, the softest blue.

The breeze was gentle,

The horses magnificent

And women stunning.

The traveller on his journey came across a land that was more beautiful with every step, each dwelling more pleasant than the last.

Guéno had blessed the land with heavy rains, but the rains did not harm the crops nor spoil the harvest.

Tornadoes blew without a clap of thunder. Lightning struck without a single tree burning down, let alone a house catching fire. All evil was unknown in this land.

The people sang songs of praise to Guéno, thanking him for his bountiful grace and for making their land of no small significance.

They believed that the great Prophet Solomon (14) himself, from whose wife Balqis, the Queen of Sheba, Aunt of the Fulɓe from whom they considered themselves descended, had drawn up the plans of Heli and Yoyo. The genies whom Solomon had enslaved accomplished many wonders and their works were no small feat.

Indeed, it is in this paradise country where the descendants of Hellêrè, son of Bouytôring, ancestors of the Fulɓe and owners of large herds (15) lived!

The silatigis (16), who have observed, studied and understood a lot, do not all agree on where the country of Heli and Yoyo was. Some have located it east of the Red Sea, in the country of Aunt Balqis, the Queen of Sheba. Others claimed that it was west of the Red Sea, between the country of the Habasi (Ethiopia) and the country of the Pharaoh King of Misra (Egypt).8

*

This tale is not intended to establish the truth or falsity of these words. In any case, a multitude of multitudes can say that the lie is the truth, but the lie will remain a lie! A multitude of multitudes can say that the truth is a lie, but the truth will remain the truth!

This tale was told to instruct the Fulɓe, so that they would not forget the distant events that caused the ruin of their ancestors, their emigration and dispersion throughout the lands; so that they would know their country of origin in this world, even if they cannot locate it in space; so that they might learn why they have been pushed back, why they wander everywhere and have become perpetual campers and decampers, spurned nomads outside the perimeter of villages, but though spurned they do not hesitate to strike down with their spears those who disdain them, to enslave those who offend them and to amaze the rulers who despise them.9

When a Fulɓe is enslaved, he accepts and knows how to wait until the day when he is sure to take his revenge.

The Fulɓe do not allow themselves to be perturbed. If they are treated badly, they start by burning their straw hut to show that they have nothing to lose, and then they set fire to that of their enemy. They wound, kill, and then leave the country with their herd because nothing can hold them back anywhere.10

10 Their only wealth is livestock and they travel with them. They retain them by honouring them.

Wilder than a tempest, they avenge their wrongs without commotion. They value honour and consideration, sometimes more than their own lives.

Whoever touches a Pullo, let it be for peace, otherwise he will find his reward!

The Fulɓe have no hoes. It is with the hooves of their horses that they dig plots in the ground.

The Fulɓe staff is deadlier than the gun.

What triggers their anger is to touch their herd, which is their wealth, or the adornments of their women,11 which is their honour. Whoever comes near them, they will make them bite the dust.

11 It is not a question here of jewels or trinkets, but anything and everything which is of moral value to a woman: her adornments are her qualities.

Endnotes:

5. Men of Knowledge: Among the Bambara, a distinction is made between soma and doma, the latter being superior to the former. The soma, for example, will simply know the various categories of plants, minerals, etc., while the doma will be able to diagnose disease and prescribe the appropriate plants. When it comes to applying knowledge, the soma will refer to the doma.

Among the Fulɓe, the gando is both soma and doma. The silatigi (sometimes transcribed “silatigui” to make it easier to pronounce) is a gando, but higher still than the latter in the hierarchy of initiation. The title of silatigi designates a degree in the initiation, which might elsewhere be called “Great Master” (see endnote 16).

6. Water lily: In the Mandé, the water lily flower symbolises the virgin ready to be impregnated. As such, it is compared to a cosmic cup waiting to be filled. The first rains of the year are regarded as heavenly seed that comes to fill this cup. For the Fulɓe and certain sects of the Mandingo religions, this flower symbolises love; it has a close affinity with conception. The Fulɓe and Dogon consider the water lily flowers as symbolic of mother’s milk; therefore, they use the leaves of this plant to help breastfeeding mothers to have plentiful milk. They do the same for the female animals. The water lily also symbolises pure birth and morality without stain.

According to Fulɓe legend, the silatigis invoke the “water lily of the ancestors” whose seeds were brought from Egypt by ancient diasporas. The women of Heli and Yoyo wore a garland of water lily flowers around their necks and decorated the braids of their hair with this flower.

7. Silk-cotton trees, baobabs and mahoganies: Footnotes concerning the meaning of these trees, as well as of some of the other plants or animals mentioned, appear throughout the narrative when any of these elements appear.

8. Water, the soulless mother element: The four “mother elements” are water, fire, air and earth. Their combination is supposed to have given birth to all contingent beings. The expression “soulless” is only meant in comparison with the human soul, because in African tradition everything has a soul: there is a mineral soul, a vegetable soul and an animal soul. These are called “the three souls”, each kingdom having a unique soul. The example of electricity can help to understand this concept of a unique soul: whether the current passes through a 25-watt lamp or a 2,000-watt lamp, it is always the same electricity. Only the power of the receptacle differs. Humans are different because they have been made to be the interlocutor of Guéno (or Mâ-n’gala). As a synthesis in miniature of everything that exists in the universe, animated by God’s breath, humanity is both the Manager and Guarantor, in the name of Guéno, of all creation. Hence his responsibility.

9. River: Rivers symbolise initiation. While initiation leads the neophyte to knowledge and wisdom, the river leads to the salt sea, so the latter is understood to represent the reservoir of knowledge. Whenever the purpose mentioned is associated with salt, it means that there is a great initiation there.

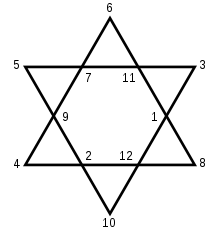

10. The Septenary Land: In fact, this whole tale is imbued with the auspices of the number seven, beginning with the very name of Njeddo Dewal which means “the septenary woman”.

The number seven is a major number in many traditions, along with the numbers one and three. Odd numbers, called “masculine”, are supposed to be more “charged” than even numbers, called “feminine”. The number seven is linked to the concept of cycles of repetition, and therefore to the concept of time. The Fulɓe say: “Every seven years”. In Islam, the multiples of 7 (70, 7,000, 70,000) symbolise a very large quantity, even something immeasurable. It should be noted that the Fatiha, the first chapter of the Koran which forms the basic canonical prayer, is composed of seven verses. Also the Christian Lord’s Prayer petitions God seven times.

In Fulɓe tradition, as in Bambara tradition, each of the seven openings of the head (the mouth, the two eyes, the two nostrils, the two ears) is the gateway to a state of being and to an inner world, and each is guarded by a particular deity. Each door gives access to a new inner door, and so on ad infinitum. These seven openings of the head are related to the seven degrees of initiation.

11. Tamarind tree: This tree with its purgative properties is the basis of African medicine. Its various parts are used in almost all traditional medicines. It is a sacred tree in the Bambara traditions of N’domo and Korê, symbolising multiplicity and renewal. Its roots symbolise longevity. When a man is seriously ill, he is told: “Grasp the roots of the tamarind tree”. Grasping the roots of the tamarind tree means triumphing over illness.

12. Male hen: cockerel / rooster. In Black Africa, the rooster is a typical sacrificial animal. They are sacrificed for the gods or in honour of a host. Because it announces the light of the new day, the Fulɓe call it the “muezzin of the animals”. It symbolises the awakening of the spirit. Its voice indicates the way that leads to the light of Guéno. All the parts of the rooster’s body have magical uses in African traditions because of their beneficial properties. Its spurs symbolise the weapon of the hero who has defeated his enemies. It is thanks to a magically worked spur that Soundiata, the hero of the Mandé, triumphed over his enemy Soumangourou. In Fulɓe tradition, the rooster is linked to esoteric secrets (see the initiation tale Kaydara).

13. Cattle: For the Fulɓe, cattle breeding had no economic purpose. The Fulɓe considered the bovine as their relative, their brother. They did not kill, sell or eat it. They consumed its milk and butter and exchanged it for other basic products. For more information on the cult of the bovine and its symbolic function among the Fulɓe, we refer to the initiation tale Koumen.

14. Solomon: In their legends and historical traditions, the Fulɓe constantly allude to events from the time of the Prophet Solomon, who is referred to as a Master and the source of certain initiations. Moreover, the Fulɓe call the Queen of Sheba “Aunt Balqis”. Some theories about the origins of the Fulɓe conjecture an ethnic kinship with the Hebrews, others with the Arabs. In their own legends, they say they have “come from the East”; see the initiation tale Radiance of the Great Star (p. 51 of the original French edition); see also the end of endnote 6. Other theories, based on linguistic studies, trace them back to proto-Dravidian India (see La Question peule by Alain Anselin, Karthala). Whatever the case may be, the rock engravings found by Henri Lhote in the Tassili caves would seem to attest to their presence in Africa since at least 3000 BC (see also Amkoullel l'enfant peul, pp. 18-19, or in the Babel edition pp. 20-22).

15. Description of Heli and Yoyo: This description raises many questions. It shows that although the Fulɓe are indeed “owners of large herds”, they live in villages or even large cities, and that their homes are “each more beautiful than the next”, which hardly corresponds to the essentially nomadic character of this people, of whom it is said on the following page that “nothing can hold them back anywhere” and that they are “more vagabond than the cyclone”. It is true that the Fulɓe settle near certain villages during the dry season, but their habitat, generally made up of precarious straw huts, is always situated outside village limits and this cannot be said to constitute a real sedentary lifestyle. The foundation of certain empires led to the creation of towns and villages, but this is a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of the Fulɓe.

Should we conclude from this account that, in the very distant past, the Fulɓe lived a different kind of life in an unknown country and that nomadic life was a later phenomenon? Or is this description an influence of the traditions of the Mandé people, with whom the Fulɓe lived in relative symbiosis (see endnote 1)? Behind the borrowings and reciprocal influences that are difficult to disentangle today, the fact remains that the Fulɓe people remember a distant and terrible cataclysm that drove them out of a marvellous country where men not only lived happy and fulfilled lives, but where they had attained a high degree of knowledge and know-how. It is said: “The only thing that the Fulɓe of Heli and Yoyo could not do was to walk a horse on a wall or bend a well to drink from it like from a glass!" Whether myth or reality or a mixture of the two, this story evokes the myth of a Golden Age or lost paradise, which is common to almost all the traditions of the world.

16. Silatigi: The silatigi is the great initiated master of the Fulɓe shepherds. As the spiritual leader of the community, he is the master of the pastoral secrets and mysteries of the bush. Generally endowed with supernatural knowledge, he presides over ceremonies and takes decisions in all matters relating to the transmigration, health and fertility of livestock. He represents the supreme stage of initiation. Every initiated shepherd dreams of one day becoming silatigi. Kournen is the initiatory text which describes the steps followed by Silé Sadio to become silatigi. In The Radiance of the Great Star, a tale set after Kaydara, Bâgoumâwel (who appears in this tale as a young boy) will be the figure of the exemplary silatigi, the master initiator of a king.

Among the traditional Fulɓe of the past, who were essentially nomads, the spiritual and temporal leadership was in the hands of the silatigis. The arbe (sing. ardo) or guides of the herd were appointed every day by the silatigis according to the omens. Little by little, especially after conquests and the relative sedentarisation that they entailed, the command passed into the hands of the arbe who became chiefs and temporal kings, the silatigis retaining only their function as initiates and master initiators. However, there are still some cases where the ardo village chief was at the same time silatigi: that of Ardo Dembo, for example, from the village of Ndilla, Linguère circle (Senegal), to whom I owe my pastoral initiation and the Koumen text.

Translation from Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Contes initiatiques peuls

Painting: Claude Monet, The Water-Lily Pond